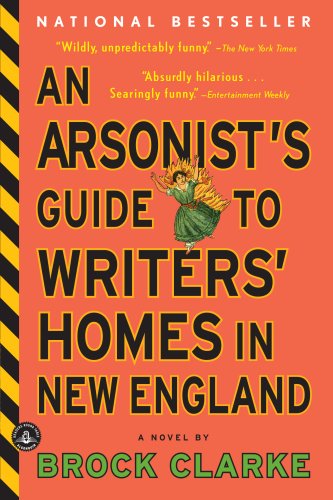

An Arsonist's Guide to Writers' Homes in New England by Brock Clarke is the perfect start-off-summer-reading-strong choice.

An Arsonist's Guide to Writers' Homes in New England by Brock Clarke is the perfect start-off-summer-reading-strong choice.As long as you don't mind coming off of your first summer read feeling not-so-warm-and-fuzzy.

The title of this novel (the brilliant title) suggested to me that the novel would be quite funny, with lots of literary inside jokes about Emily Dickinson and H.D. Thoreau to make us literary-types feel oh-so-clever and smug when we're done.

Not so much.

Instead, it reminded more of a John Irving novel (see the Must List), though with fewer perverted sex acts ending in violence.

What I mean by this is that as the protagonist bumbles his way through the plot (and I use this word intentionally, more on that later) this reader was led to wonder, "is there anything worse that can happen to this guy?" And, as with Irving, the answer is always yes.

Sam Pulsifer is an unreliable narrator to make Gene Forrester look downright dependable. (Click that link; I find it hilarious.) Sam pulls frequent Jane Eyres in attempts to explain himself to his audience, but his reassurances just made me trust him less. So the first-person Arsonist's Guide may be Sam's autobiography, it may be his novel, or it may be his autobiography ghost-written by a group of bond analysts with whom he spent ten years in minimum-security prison who now seek to blackmail him in order to turn a profit off of his disastrous misadventures. Half-way through the novel, Sam is approached by Morgan and G-off, the aforementioned bond analysts, who petition him:

Morgan said, "We want you to tell us how to burn down houses like the one you burned down. And after we do, we can write a book about it."

"An Arsonist's Guide to Writer's Homes in New England," G-off said. "We've already come up with the title."

Yeah.

So there's literal arson in this story, but I think, (and this is what makes me like it/bothers me about it) that its really much more about whether or not stories themselves should all be torched, since Sam/Brock seems to think they mostly just cause problems anyhow. Sam burns down a house, yes, and many other literary abodes go up in smoke throughout the novel, but Sam contends that it was a story that was actually to blame for the accidental conflagration that killed two people and changed the course of his life.

Rather than using literary allusion to make us readers feel like cool insiders, Brock instead mocks every piece of reading culture us book-bloggers hold dear. Sam encounters a Lit prof who doesn't "believe in literature,"an English teacher who is through with books, a book club that discusses everything but, and a late-night meeting of men and women dressed as witches and wizards whom he fears are Wiccans but turn out to be clutching "one of those children's books out of England." (Incidentally, Brock uses overwhelmingly famous examples of literary popular culture without naming them several times; a trick that I found particularly delightful.)

The professor and the teacher have shunned books because, as the professor puts it, she "[doesn't] want to be a character in the book my students are reading." She goes on, "I don't want to be the hard-bitten character who had endured tragedy and come out a better, more sympathetic person" (148). They seem to have been so negatively affected by books that they need to literally escape from them.

On the other hand, the even crazier book clubbers and wizards seem to operate under the delusion that there is something to be found in fiction that might actually make their lives better. They don't need the book so much as they need the object of the book to give themselves a place to put their problems. As the witches and wizards depart from their late night meeting, "there was a long sincere discussion about how very magical fog was and how they'd be sure to wake up their kids ... to show them the fog ... and then they'd compare the literary fog and the meteorological fog ..." (174). It's obvious Sam thinks this is a pretty dumb idea.

If all of this is confusing, well, yeah, it is. I have no idea what side Sam/Brock/the bond analysts want us to come down on. As the judge who sentenced Sam asks during his trial,

"Can a story be good only if it produces an effect? If the effect is a bad one, but intended, has the story done its job? Is it then a good story? If the story produces an effect other than the intended one, is it then a bad story?"

Not to be too cute, but I haven't decided if this novel is a good story or a bad story. But it's worth spending time reading either way.