Having had a conversation, often in hushed tones, about Fifty Shades of Gray with everyone from my colleagues to my closest friends to my physical therapist, I've been thinking a lot lately about what makes something catch fire (forgive the pun) in the public imagination the way Shades and Hunger Games have recently. It's not that I question the appeal of these texts: epic and dystopian tropes and, well, sex, don't need analysis here.

I understand why Hunger Games captures and entrances us. But why don't more people realize that the feelings these texts evoke are the feelings that any fully-realized and even passably well-written world has to offer?

Having spent two very happy days of summer vacation lost in Veronica Roth's 2011 YA novel Divergent, I assure you, Dear Reader: Hunger Games is magic. But its magic is the magic of books and stories, nothing more secret or hard to come by, but every bit as sacred.

I enjoyed but never loved Hunger Games. But, despite its imperfections, I loved Divergent. Its heroine, Tris, is real and powerful, and she doesn't take herself too seriously, (At one tense moment she reminds herself: That is all I need: to remember who I am. And I am someone who does not let inconsequential things like boys and near-death experiences stop her.) and to my mind, she quickly becomes comfortable with her own power and agency in an easy manner that Katniss takes forever to embrace.

Divergent is smart, and so is Roth, who describes Tris's world as the result of her desire to write about "a subculture of people who want to eradicate fear using exposure therapy." (Curious? Read it.) When asked about writing Tris herself, Roth explains, "I did set myself a rule that was hard to follow, though: Tris is always the agent."

Stephenie Meyer, eat your heart out.

The world of Divergent yields its secrets at a satisfying pace, Tris's love interest is more worthy than Gale and Peeta put together, her relationship with him more real, and in the first book, Tris upsets the system of her world itself in a way that I longed for Katniss to attempt much sooner than she eventually did.

Tris wouldn't have won the Hunger Games. She would have made her own rules.

Monday, June 18, 2012

Tuesday, June 12, 2012

Dune, by Frank Herbert

Ever since I discovered Battlestar Galactica last winter, I've been fairly convinced that I missed something pretty big in terms of Science Fiction throughout high school and college. This winter, it was Patrick Rothfuss's incredible Kingkiller Chronicles.

If Lord of the Rings turns you off, and you can't recite most of the lines from The Empire Strikes Back by memory (hint: it's usually "I've got a bad feeling about this...") then don't bother. But if you haven't picked up Dune in a while, or at least one of these titles above gives you the shivers, it's worth revisiting. Like all great epic tales, Paul's obstacles become the readers own.

In Dune, by Frank Herbert, Paul Atreides faces the perils of life on Arrakis, or Dune, the planet George Lucas used to inspire Luke's home-planet Tatooine. After the assassination of his father, the Duke Leto Atreides, Paul and his mother, Jessica, escape the hostile usurping forces and join the Fremen, the blue-on-blue-eyed natives of the harshest parts of that desert world.

Paul will remind you of Luke, as well he should, with his Arrakian-exceptionalism and his pithy understanding of both future and past, and I found myself similarly moved and compelled by him. In a novel driven by economics, politics, yes, even jihad, (Interestingly, much of the Freman languauge is nonsense Arabic -- fascinating in a book published in 1965 and read today) Paul is at once strong and completely vulnerable. And so, like Luke and Kara and Harry and so many others after him, Paul faces his destiny.

As Paul begins to take his final steps towards fulfilling his fate, Freman tradition dictates that he must challenge Stilgar, friend, mentor, and current leader of the tribe. But as Paul faces his old friend, he asks:

“Do you think you could lift your hand against me?”

Stilgar began to tremble. “It’s the way,” he muttered.

As Stilgar remained silent, trembling, staring at him, Paul said:

“Ways change, Stil. You have changed them yourself.”

Perhaps the role of these narratives is to remind us that ways change, and yet, they remain the same. We readers love to find ourselves in the role of these heroes who must decide what can endure in times of tumult, perhaps because they are so similar to, and so different from, the times of challenge and revolution in our own lives.

Dune reminds us that what is most important, be it epic narrative itself or something as simple and commonplace as a friendship, will remain, even as we change our lives to meet our own destinies. Paul may be exceptional, but he reminds us that, assuredly, so are we.

If Lord of the Rings turns you off, and you can't recite most of the lines from The Empire Strikes Back by memory (hint: it's usually "I've got a bad feeling about this...") then don't bother. But if you haven't picked up Dune in a while, or at least one of these titles above gives you the shivers, it's worth revisiting. Like all great epic tales, Paul's obstacles become the readers own.

In Dune, by Frank Herbert, Paul Atreides faces the perils of life on Arrakis, or Dune, the planet George Lucas used to inspire Luke's home-planet Tatooine. After the assassination of his father, the Duke Leto Atreides, Paul and his mother, Jessica, escape the hostile usurping forces and join the Fremen, the blue-on-blue-eyed natives of the harshest parts of that desert world.

Paul will remind you of Luke, as well he should, with his Arrakian-exceptionalism and his pithy understanding of both future and past, and I found myself similarly moved and compelled by him. In a novel driven by economics, politics, yes, even jihad, (Interestingly, much of the Freman languauge is nonsense Arabic -- fascinating in a book published in 1965 and read today) Paul is at once strong and completely vulnerable. And so, like Luke and Kara and Harry and so many others after him, Paul faces his destiny.

As Paul begins to take his final steps towards fulfilling his fate, Freman tradition dictates that he must challenge Stilgar, friend, mentor, and current leader of the tribe. But as Paul faces his old friend, he asks:

“Do you think you could lift your hand against me?”

Stilgar began to tremble. “It’s the way,” he muttered.

As Stilgar remained silent, trembling, staring at him, Paul said:

“Ways change, Stil. You have changed them yourself.”

Perhaps the role of these narratives is to remind us that ways change, and yet, they remain the same. We readers love to find ourselves in the role of these heroes who must decide what can endure in times of tumult, perhaps because they are so similar to, and so different from, the times of challenge and revolution in our own lives.

Dune reminds us that what is most important, be it epic narrative itself or something as simple and commonplace as a friendship, will remain, even as we change our lives to meet our own destinies. Paul may be exceptional, but he reminds us that, assuredly, so are we.

Sunday, June 10, 2012

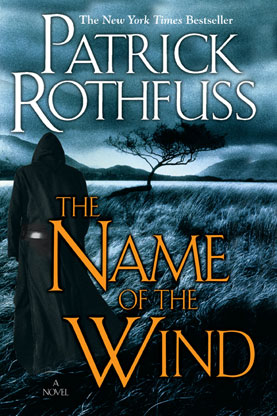

The Name of the Wind, The Lonely Polygamist, and Freedom

More cerebral than Game of Thrones, more grown up than The Golden Compass, and with a protagonist with enough hubris to make Han Solo look modest, The Name of the Wind is transporting. And at 800-plus pages with a 1000 page sequel in The Wise Man's Fear, it will keep you busy for a week at the beach or for many delicious late-nights.

It tells the story of Kvothe, son of troupers Edma Ruh, prodigy archanist, and hapless lover, as he becomes Kvothe the Bloodless, building a reputation at the University and seeking to revenge his parent's brutal murders.

I recommend this one to fantasy nerds without exception or reservation. If you run more mainstream give it a try, but only if you're looking to commit some time.

I am telling you here and now: The Lonely Polygamist by Brady Udall is one of the greatest novels of the twenty-first century. And not because Sister Wives is hot right now. This is, quite simply, one of the funniest, most moving, most gorgeous books I've ever read, and it has been compared to Catch-22 by people who know. It does not serve to expose the strange lifestyles of the Mormon and polygamist. Rather, it paints its characters with deep sympathy and pathos.

And it is devastatingly, heart-rendingly funny.

This book is now at the top of my Must List. It is too good to miss, it will change you in the way that all great books change you, and please tell me once you've read it. Trust me, you'll want to talk about it.

I know, Freedom by Jonathan Franzen is no news. But hear me out on this one. I bought it when it came out, and it sat on my bookshelf for ages. But my best friend from high school, who freely admits that she rarely reads fiction, recommended it. I opened it on a Saturday and lost myself. And even though I read it in January, I think of it more regularly than any other book I read this year.

It is so devastatingly incisive about modern life, so vividly written, so horribly funny. And the characters are despicable. If you're not particularly interested in dwelling for 1000 pages in the way literature can reveal sometimes-painful truths about ourselves and the way we live, skip it. But if you want a read that will make you feel something, that will challenge you, and yes, possibly depress you for a while, this is perfect.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)